Seven men received prison sentences totaling 174 years last week for exploiting two teenagers in Rochdale. Britain is now debating whether crime statistics should include ethnicity. While some argue this transparency helps justice, the reality is more complex.

Publishing ethnicity data risks two major harms. It turns crime into identity politics by highlighting overrepresentation, and it shifts focus away from the real causes behind criminal networks toward migration.

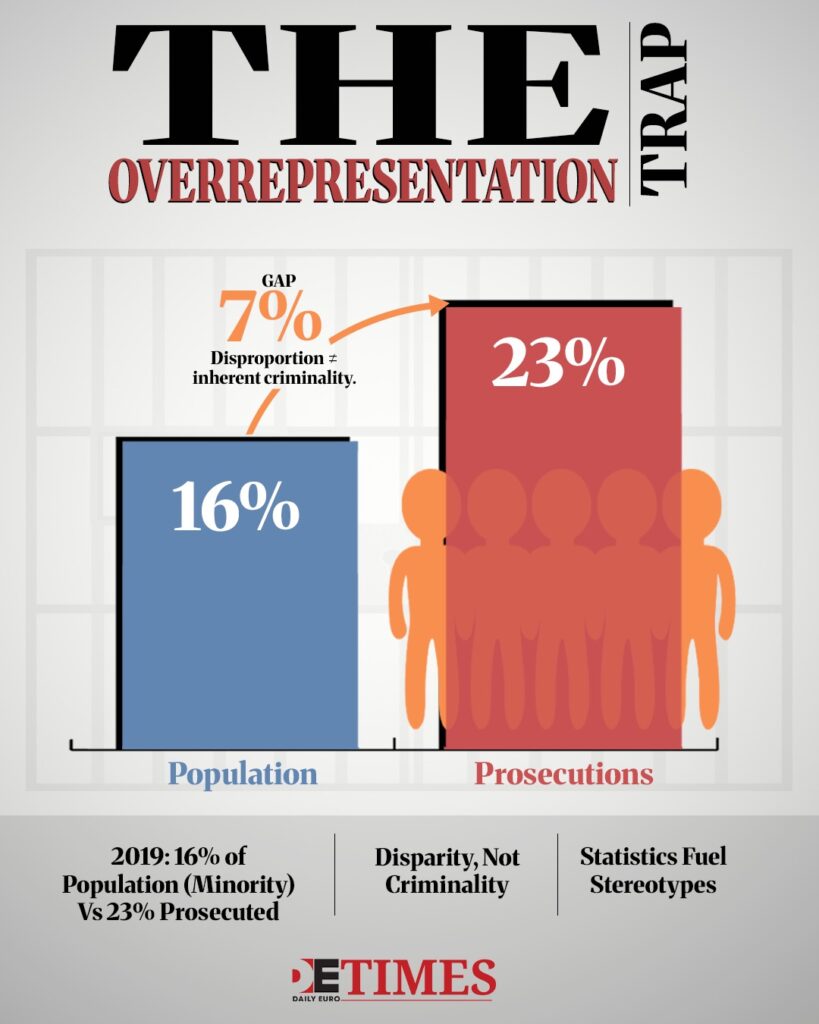

The Overrepresentation Trap

Releasing ethnicity in criminal records will inevitably produce disproportionate statistics.

Such figures already exist: in 2019, minority communities accounted for 23% of prosecutions but only 16% of the population in England and Wales.

The United States faced a similar situation decades ago. African Americans appear in arrest numbers more than their share of the population. Politicians then wrongly interpreted this as evidence of inherent criminality. This shifted the debate away from police bias toward stereotyping entire communities. Policies followed these perceptions.

The Rochdale convictions involved South Asian men. Mohammed Zahid was sentenced to 35 years as the gang’s leader, while six others received 12 to 31 years each. Including their ethnicity in official stats risks turning individual crimes into assumptions about whole groups.

Geography Over Ancestry

In the UK, public discussion links these crimes to migration. Unlike in America, where that step was avoided, the debate becomes about who belongs instead of what conditions allow exploitation to thrive.

Gangs form based on proximity and opportunity. Criminal behaviour is learned through social interactions and local culture.

Historically, American urban gangs were formed by white ethnic groups like the Irish and Italians until the 1960s; ethnicity shifted over time, but the gang structure stayed the same.

The Rochdale network operated through local markets and relationships. Shared heritage provided trust, but geography and chance created the environment for the crime.

Structural Factors Vanish

Research shows that disproportionate prosecution doesn’t mean some groups are naturally more criminal. Instead, systemic bias and social problems play roles.

Poor housing, school exclusions, poverty, and unstable jobs increase vulnerability. Publishing ethnic data alone cannot reveal these deeper causes.

Policing also varies by area. Black individuals face prosecution rates 16 times higher than others under certain laws. The law is applied unequally even before crimes are committed.

Ethnic breakdowns in statistics risk fueling demands for stricter immigration policies while avoiding tough conversations about institutional failures.

How did abuse in Rochdale go unnoticed for years despite warnings? What economic situation allows market traders to lead gangs? These are complex questions without easy answers.

The American Preview

The U.S. experience is a litmus test gone wrong.

Ethnic crime data was used to justify mass incarceration and harsh policing, disproportionately targeting communities of colour. Yet underlying issues like poverty, education gaps, and employment discrimination continued unchecked. Arrest numbers rose while social problems persisted, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

In Britain, 51% of offenders under-18 come from minority backgrounds. This fact is linked to policy choices and institutions, not ethnicity alone.

What Data Obscures

Criminal gangs need specific conditions to exist. Economic hardship breeds desperation, pushing people toward illicit income. Weak social services fail to protect vulnerable youths.

In Rochdale, systems failed repeatedly, allowing predators open routes to their victims.

Focusing on ethnicity in crime statistics distracts from these systemic failures. The conversation shifts from preventing abuse to blaming groups. Support services, community investment, and law enforcement accountability are the real priorities, not ethnic profiles.

The Majority Commits More Crime

Despite headlines on disproportionality, the majority population commits more total crimes. Publishing ethnic breakdowns often hides this fact, emphasising percentages over absolute numbers.

Media frequently reports minority overrepresentation without noting white Britons commit higher total offences. This framing turns statistical facts into broad generalizations about communities.

British politicians may use such data to push immigration restrictions instead of addressing root causes.

Local Networks Factor

Each criminal gang forms through local, personal connections. The Rochdale group united through markets and community ties. Shared heritage built trust, but geography and opportunity created the crime itself.

Statistics that label entire groups as high risk encourage profiling and collective suspicion. Real crime prevention means understanding why gangs exist in British cities today.

Questions Worth Asking

Why do vulnerable children go unprotected? What economic problems allow criminal networks to flourish openly? Which institutional failures let abuse persist for so long? These important questions don’t get answered by ethnic statistics alone.

Seven men committed terrible crimes in Rochdale and will serve long prison terms. The legal system eventually worked, though slowly. Publishing ethnicity will not stop future abuse; it risks fueling division instead.

The data could be used either to expose systemic failures or to scapegoat minority communities. One path offers hope to reduce crime. The other spreads discrimination.

The recent convictions should prompt reflection on institutional accountability. Knowing criminals’ ethnicity does not explain how to prevent crime. Understanding the circumstances that enable it does. Publishing ethnic data serves political aims more than public safety.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates!

Read also:

New Troubles: Northern Ireland Vigilante Crisis

A Match to a Flame: Reform UK and Immigration

On the Back Foot: UK Cracks Down on Grooming Gangs