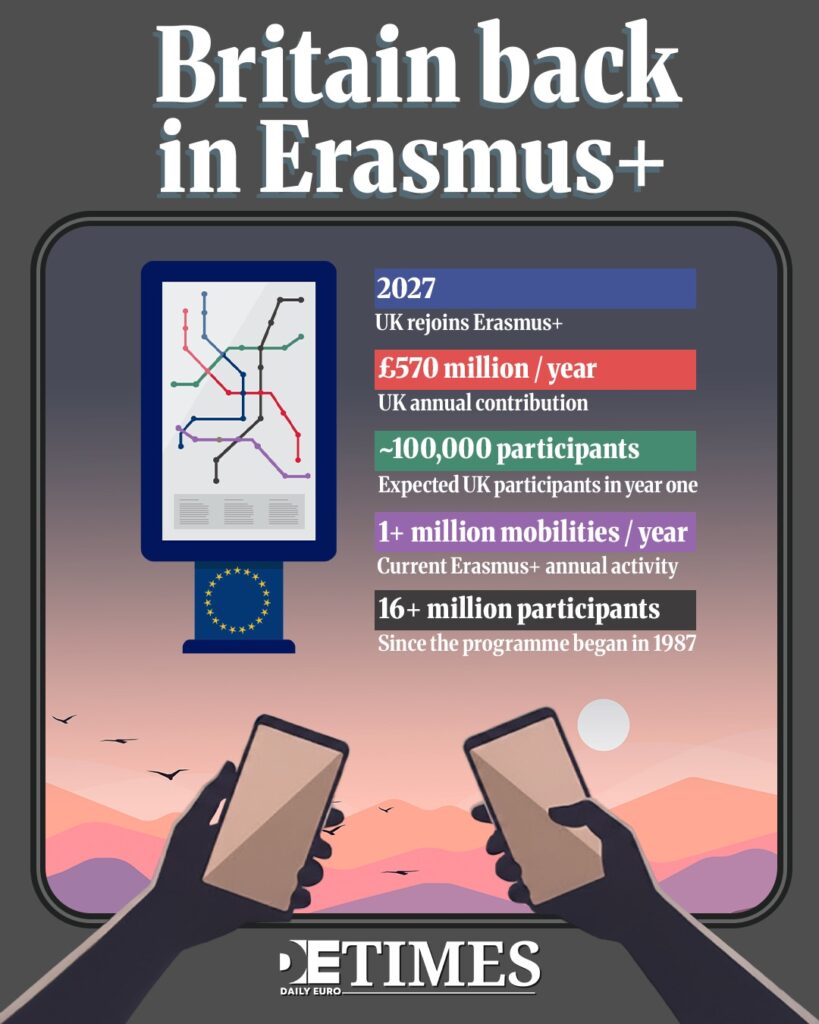

In December, the UK and EU agreed that Britain will re-enter Erasmus+ from 2027, with an annual contribution of around £570 million and an expected 100,000 participants in the first year.

It comes as Erasmus+ itself reaches record numbers, funding over a million mobilities a year and more than 16 million participants since 1987.

For many, the return of a major country to the scheme feels more than administrative. It suggests that physical exchange still matters, even in an age that starts most friendships on a screen.

From Elite Perk to Wider Access

Erasmus+ began as a scheme for a relatively privileged group of university students. Over time it expanded to include vocational trainees, apprentices, teachers and youth workers.

In 2023, over 200,000 participants were classified as having “fewer opportunities”, including migrants, people with disabilities and those from remote or low-income backgrounds. That shift altered the programme’s image.

It is no longer only the cliché of wine-fuelled semesters in Paris, but also short placements, school exchanges and training courses that can change careers. Yet access gaps remain.

Students from wealthier families still find it easier to move abroad, and short-term placements can reproduce existing inequalities rather than reduce them.

Beyond Borders and Timelines

Research consistently finds that participants report a stronger sense of connection after their time abroad. They tend to become more comfortable working with people from other cultures and more likely to vote in elections.

But Erasmus+ now extends beyond its original membership. Partner countries around the southern shore, including Algeria, Morocco, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Tunisia, take part in joint projects and mobility schemes.

For students from southern cities who move north, and for young people from North Africa who join virtual or physical exchanges, the programme becomes a laboratory of contact rather than a purely intra-bloc club. This wider geography quietly challenges the idea that identity stops at certain borders.

It also raises practical questions: how to avoid brain drain from already fragile universities, and how to ensure that cooperation flows both ways rather than only pulling talent inward.

Online Lives, Offline Encounters

Today’s cohort grew up with cheap flights, video calls and social media. Many already have friends in other countries long before they pack a suitcase.

That reality sometimes fuels the argument that physical mobility is less necessary. If language tandems and gaming servers connect teenagers across borders, why invest billions in train tickets and rent subsidies?

Yet surveys suggest that living abroad still changes attitudes in ways that online contact does not. A semester in another city forces students to navigate new bureaucracy, overhear everyday conversations and encounter different versions of normality.

Those banal details of life abroad rarely appear in curated feeds. For young people in the Middle East and North Africa taking part in Erasmus-linked virtual exchanges, blended formats that combine online and short physical stays may become the compromise amongst cost, emissions and depth of contact.

Promises and Conditions

A revived Erasmus+ will not fix divides, nor guarantee peace. It will, however, keep offering something that algorithms cannot yet produce: structured encounters with difference that last long enough to move beyond stereotypes.

In an era that often rewards retreat into national comfort zones, programmes that ask people to live elsewhere for months at a time feel almost radical. They demand patience, paperwork and the willingness to be a beginner again in another language.

If governments want Erasmus+ to remain more than a nostalgic logo, they will have to make sure that those benefits reach vocational students, apprentices and young people outside the usual elite circles, including in partner countries to the south and east.

After four decades, the strength of Erasmus+ may lie not in producing perfect citizens, but in normalising the idea that crossing borders to learn is part of an ordinary life.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates.

Read also:

Universities Pay the Price for Anti-Migration Politics

Britain vs Big Tech: Can the Online Safety Act Really Govern the Global Internet

Caspian Bottleneck: All Roads Lead to Baku