When a Picasso vanished en route from Madrid to Granada in early October, investigators expected a theft. Instead, they found an absence. According to Spanish authorities, Naturaleza muerta con guitarra never boarded the transport van.

The 1919 still life, valued at €600,000 and owned by a private collector, disappeared somewhere between a Madrid storage depot and the exhibition truck bound for the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Málaga. The case resolved after eighteen days when the painting was recovered on 24 October.

It ended less dramatically than it began, but exposed an uneasy truth about Europe’s art world. Even in an age of sensors, registries, and digital archives, masterpieces still depend on paper logs and human oversight.

Officials described the incident as a packaging error. The work may not have been loaded onto the truck before departure from the Madrid facility where private collectors’ works were gathered. The painting was found undamaged. Yet the public reaction revealed something larger than logistics: a crisis of cultural trust.

When Art Moves, Faith Follows

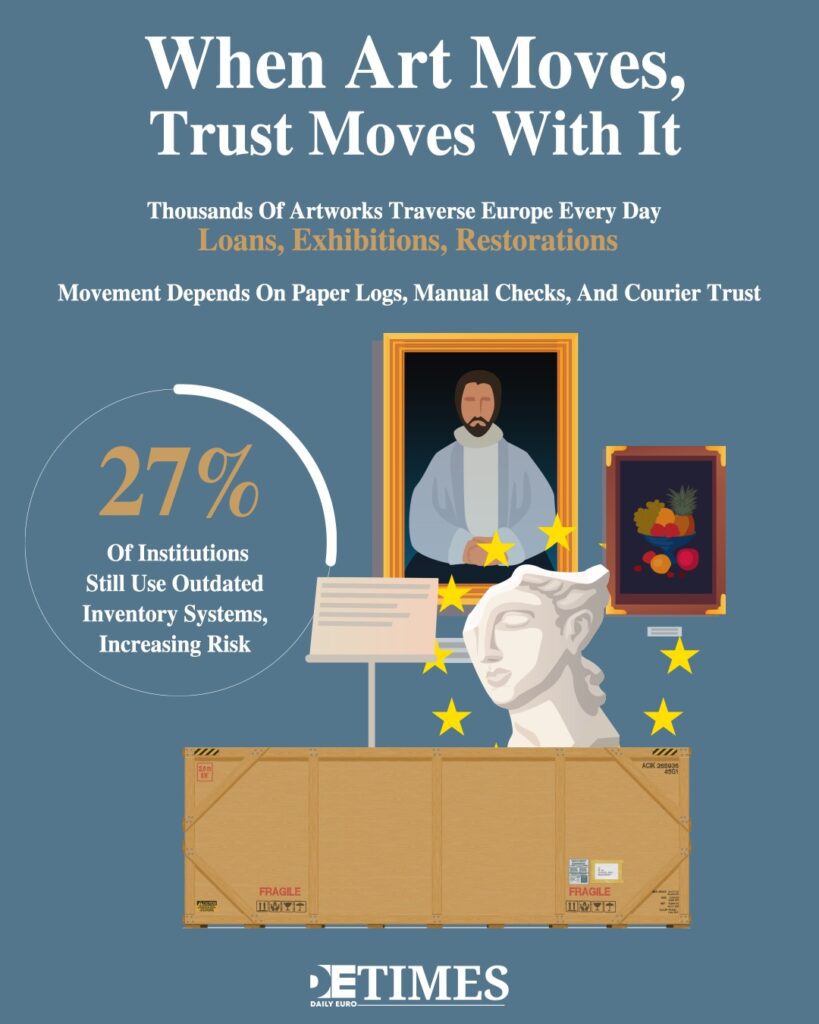

Every day, thousands of artworks travel across Europe for loans, restorations, and exhibitions. They are carried in sealed crates, escorted by couriers, and tracked through a patchwork of national systems. The Picasso incident is a reminder that this vast network of movement functions mostly on trust.

The Art Newspaper reported in 2024 that the European museum sector faces chronic underfunding for transport security. Twenty-seven per cent of institutions use outdated inventory technology. The European Commission’s Cultural Heritage in Action programme has urged tighter standards, but national systems still vary widely.

The irony of a still life that never moved struck a chord with curators. It shows how even small procedural gaps can unsettle the idea that museums and private collections are infallible custodians.

Beyond Blame

Spanish cultural authorities have promised improved tracking protocols for art shipments involving private collections. The transport sector, which handles works from both public and private sources, has faced scrutiny over coordination between different parties in the art-loan process.

The problem lies not in malice but in scale. Europe’s museums and private collections manage millions of works, many in rotation or on loan. Each crate, manifest, and restoration request passes through countless hands. Transparency and traceability remain ideals more than realities.

Some institutions now explore digital provenance systems using blockchain to verify movement and authenticity. Others call for a shared European database to prevent similar confusion, echoing proposals discussed at the Council of Europe’s Cultural Routes conference last June.

What the Incident Reveals

Art thefts often make headlines because they seem cinematic. Yet the more mundane errors, such as mislabelled shipments or forgotten crates, reveal how vulnerable heritage really is. They remind us that preservation is less about walls and alarms than about the people who guard culture quietly every day.

Picasso’s rediscovered Naturaleza muerta con guitarra will travel again, this time under tighter watch. Its brief disappearance became a parable about fragility: art’s safety depends not only on locks and paperwork but on human care, attention, and honesty.

As museums reopen exhibitions and circulation grows, the question remains whether trust can keep pace with technology. In the end, what vanished in this case was not just a painting, but the comforting illusion that some treasures are too important to lose.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates!

Read also:

The Louvre Robbed of Its Royal Past

Exhibitions – Daily Euro Times

Second Renaissance: Arabic Calligraphy