Spain presents itself as orderly and environmentally conscious. The recycling rate has risen steadily, the ban on single-use plastics is among Europe’s strictest and most cities boast strong commitments to sustainability.

Yet walk through the residential streets of Madrid, Valencia or Málaga and a different pattern appears. Pavements are stained with dried dog urine and dotted with uncollected faeces. Local councils spend millions cleaning public areas, but the problem persists.

New figures from municipal reports in Madrid and Barcelona indicate rising complaints related to dog waste in 2024 and 2025. Barcelona is preparing new civility ordinances expected before summer 2025, while Valladolid introduced mandatory soapy-water requirements from January 2025.

This creates a contradiction that is difficult to ignore. Spain’s international image is one of modernity and high quality of life. Its streets, however, often tell a messier version.

What the Numbers Reveal

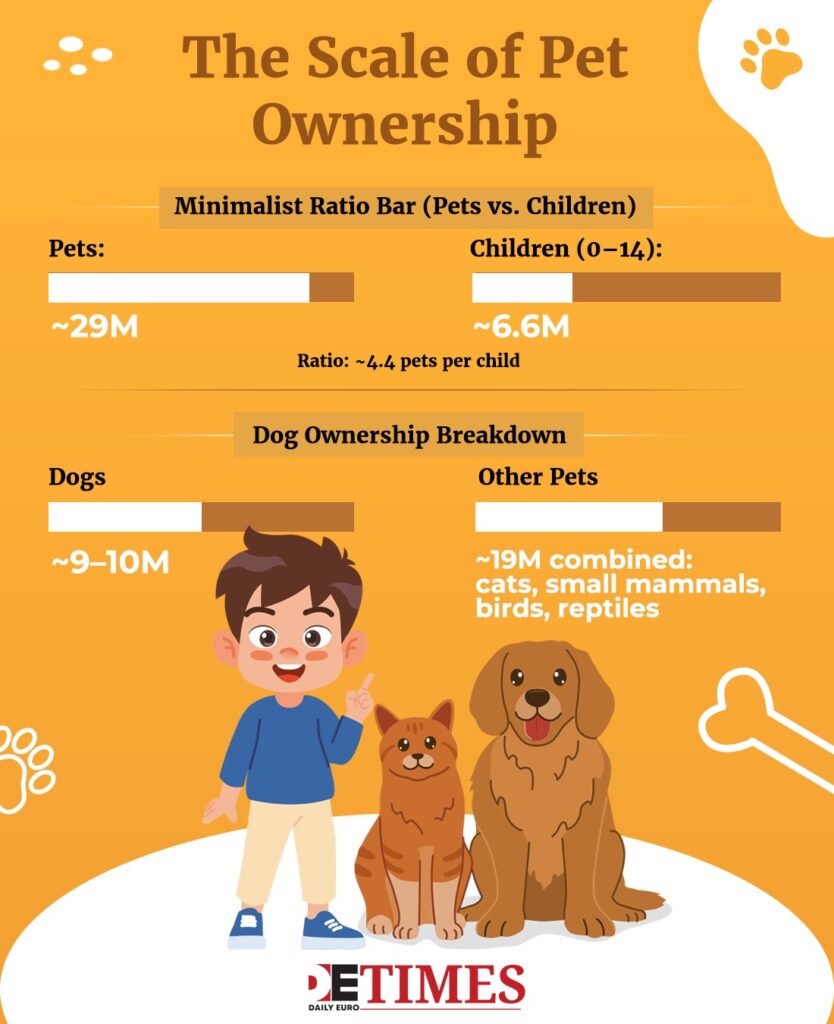

The country now has more pets than children.

Studies estimate that 29 million companion animals live in Spanish homes, with dogs representing the majority. Dog ownership surged during the pandemic, with many first-time owners unfamiliar with urban etiquette.

The Animal Welfare Law of 2023 introduced new rules, but enforcement has been limited and public behaviour has been slow to adjust.

Cities try different solutions. Barcelona is expanding its civility ordinance, Valencia continues its dog DNA registration programme and Seville has launched new cleaning systems using biodegradable detergents.

Torremolinos issued hundreds of fines in early 2024, ranging from €75 to €500. Yet the results remain uneven.

Córdoba, like many medium-sized cities, struggles to keep up, and local campaigns have little effect without consistent enforcement.

Why Spain Struggles

The issue is not unique to Spain, but the intensity of the problem is striking. Several factors converge to create this civic contradiction. Urban design plays a role. Many Spanish neighbourhoods have limited green zones and rely on pavements as multi-use space.

Yet the idea that dogs should relieve themselves freely on streets rather than in designated dog parks has led to a cultural norm that other European cities have successfully challenged.

Where dog parks exist, they are often poorly maintained or treated as optional rather than essential. The result is that entire districts function, unintentionally, as open dog areas. Cultural habits add to this. Pets are deeply loved in Spain, yet affection does not always translate into responsibility. Some owners clean up only when watched, and many ignore the need to rinse urine stains, even when required by local rules.

Enforcement remains inconsistent. Municipal agents cannot monitor every corner, and many infractions happen outside peak hours. A regulation rarely applied quickly becomes invisible.

A European Comparison

Spain is not alone. France, especially Paris, struggles with the same problem. Dog waste is regularly mentioned in city surveys as one of the capital’s top quality-of-life complaints, despite repeated municipal campaigns. At the same time, there are European models that demonstrate the issue can be managed.

The Netherlands, Denmark and Austria have built a culture in which pet ownership is tightly linked to civic discipline. There are more dog-friendly green areas, but also stronger social pressure to clean up and firm penalties for those who do not. Streets in these countries tend to reflect that collective attitude.

The contrast becomes sharper when viewed through another lens. In many Western countries, including parts of Europe, there is a persistent assumption that cities in North Africa or the Middle East are less orderly or less clean. Yet anyone who has spent time in their neighbourhoods knows the opposite is often true.

In areas with fewer pet dogs and a strong culture of shared public life, streets and squares can be notably well kept. Dust or older infrastructure is not neglect, and it is sometimes Western perceptions that lag behind reality. What this comparison shows is that cleanliness depends on habits, not on wealth or geography.

A Growing Awareness

There are positive signs.

Younger generations are increasingly vocal about urban hygiene, and neighbourhood groups have started informal awareness campaigns.

Veterinarians and training schools promote responsible walking practices. Some cafés and shops display friendly reminders at their doors. These small interventions cannot solve the issue alone but they demonstrate that a conversation has begun.

Spain has solved more complex challenges than this. The smoking ban, once controversial, transformed public behaviour in a few years. Recycling, once rare, is now routine. A shift in dog-waste culture is possible, but it requires the same combination of social pressure, public education and consistent enforcement.

The Meaning of Public Space

The heart of the issue is not hygiene but respect for shared space. A pavement is not an extension of a private home. It belongs to everyone: children walking to school, older residents using mobility aids, tourists discovering a city for the first time. When entire cities begin to function as dog parks rather than shared public environments, the basic social contract weakens.

Public space gains dignity when people feel it is truly shared, not held hostage by a minority of irresponsible owners. Spain’s struggle with dog waste is therefore more than an aesthetic inconvenience. It exposes a tension between image and reality.

The country aspires to be modern and environmentally conscious, yet some daily behaviours remain stubbornly careless.

Lessons Beyond Spain

The problem is not exclusive to the Iberian Peninsula. Many European cities face similar challenges, especially where pet ownership has grown quickly. What makes Spain notable is the difference between its reputation and the lived experience in many neighbourhoods.

The country now has a chance to correct this. With better enforcement, communication and a stronger sense of shared responsibility, Spain could narrow the gap between how it presents itself and how its streets actually feel.

Public space that feels cared for is not a luxury but a basic sign of civic respect. Spain has the resources, awareness and urban pride to fix this. The question is whether it has the will to turn aspiration into habit.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates!

Read also:

Rarity or Vanity? When Luxury Becomes Art’s Language

Spain’s Digital Nomads: The Paradox of Remote Working

Smart Cities of Scandinavia: Futuristic Urban Living