The Grand Egyptian Museum, perched between Cairo’s ring road and the Giza plateau, is one of the most ambitious cultural projects of the twenty-first century.

Conceived in 1992 and designed by Dublin-based Heneghan Peng Architects, it took more than two decades to complete.

The museum cost approximately $1.2 billion and covers 81,000 square metres of exhibition space. It sits within sight of the pyramids. Inside, visitors ascend a vast staircase flanked by colossal statues, including the 3,200-year-old figure of Ramses II.

For the first time, the complete Tutankhamun collection of more than 5,000 artefacts is displayed together. Every angle of the building seems designed to impress, from the glass façade angled towards the desert horizon to the alabaster floors that mirror the Egyptian sun.

Its opening this year marks a symbolic moment: Egypt presenting itself once more as a cultural powerhouse. Yet the museum’s journey tells a larger story about how nations in the region are reshaping their image through monumental culture.

From Heritage to Soft Power

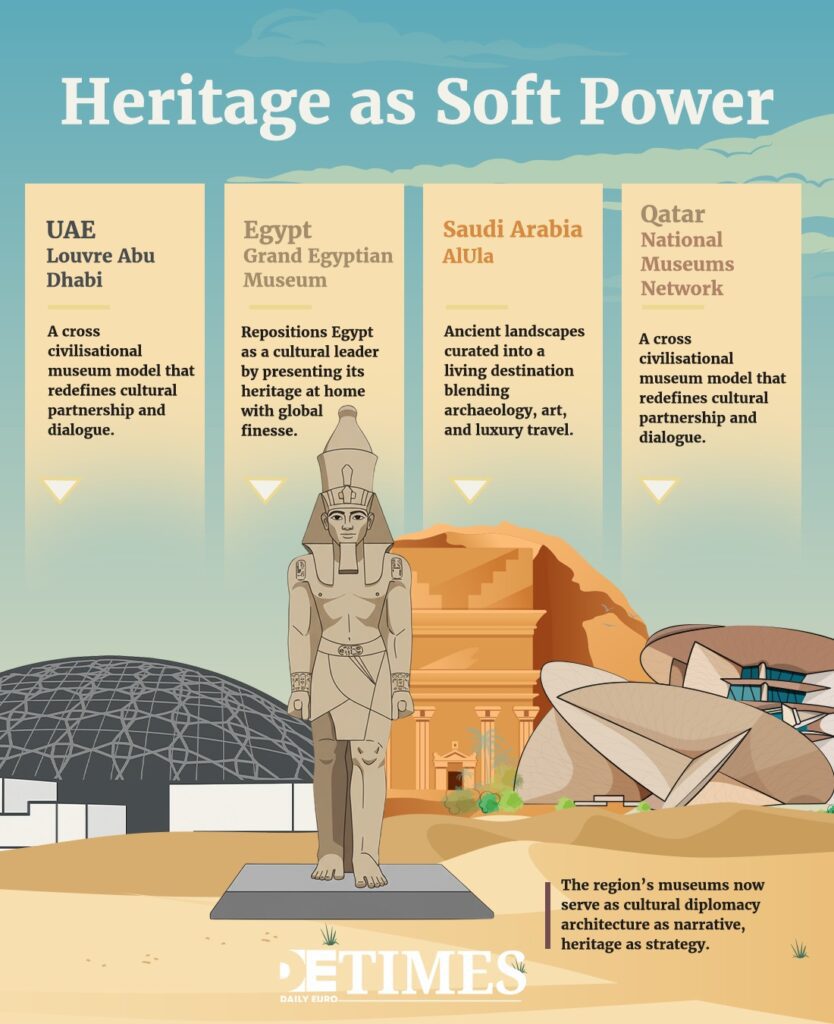

The Grand Egyptian Museum is not alone in its ambition. Across the region, art and archaeology have become instruments of diplomacy and development. The Louvre Abu Dhabi redefined how museums can bridge civilisations. Saudi Arabia’s AlUla initiative has opened ancient Nabataean landscapes to the world.

Qatar continues to expand its network of national museums celebrating both tradition and design. Egypt’s new museum joins this family of global statements: grand cultural institutions meant to reaffirm heritage while welcoming international visitors.

For Cairo, the museum is also a gesture of resilience. Construction paused after the 2011 revolution, revived with Japanese funding, and slowed again during the pandemic. That it stands completed at all speaks to endurance.

The timing also matters. With tourism accounting for about 8 per cent of GDP, Egypt hopes the museum will boost arrivals and reshape narratives about its economy. Culture becomes strategy. The government aims to attract 30 million visitors annually by 2032.

Spectacle and Substance

At the opening ceremony on 1 November, the guest list glittered: presidents, crown princes, cultural ministers, and curators from Europe and the Arab world.

King Philippe of Belgium, King Felipe VI of Spain, Prince Albert II of Monaco, and German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier attended.

Drone shows lit the sky, orchestras played beside marble walls, and speeches invoked Egypt’s eternal role as the cradle of civilisation. The spectacle was impressive, but it raised a question that now follows many of the world’s new mega-museums: how much grandeur is necessary to prove cultural worth?

Older museums once told their stories with little ceremony. The Egyptian Museum of Tahrir, dusty and chaotic, gave generations of visitors a sense of intimacy with history. The Grand Egyptian Museum, by contrast, feels carefully choreographed. Every corridor glows with precision lighting, every angle measured.

It is stunning, but sometimes distant. Yet a museum is a museum nonetheless. What matters in the end is whether people can enter, afford tickets, and see the treasures that belong to them. Accessibility, not scale, will determine whether the museum becomes a living institution or a monument to aspiration.

Between Europe and the Region

Europe has long shaped and housed Egypt’s past.

The British Museum, the Louvre, and the Neues Museum still display many of its most famous artefacts. The Grand Egyptian Museum subtly reverses that direction. It reclaims heritage by keeping it home and presenting it with equal sophistication.

In that sense, the new museum is not only a national statement but part of a quiet rebalancing. Where Europe built museums to collect the world, Egypt now builds one to display itself to the world.

The project’s international collaboration also shows how cultural dialogue continues across the Mediterranean. Irish architects, Japanese engineers, and Egyptian craftsmen have together created a space that belongs to more than one tradition.

The Value of Wonder

The Grand Egyptian Museum is vast enough to impress any visitor, yet its deeper impact will depend on how it inspires wonder. A museum’s task is not only to conserve objects but to connect people to what they mean.

In an age when culture is often used to project power, the museum reminds us that art and archaeology still carry a human purpose. They preserve the imagination of a civilisation that built in stone what others only wrote in words.

If future generations can stand before Tutankhamun’s mask or Ramses II’s statue and feel curiosity rather than awe alone, then the investment will have paid off. Great buildings attract attention; great museums sustain understanding.

Egypt’s newest monument to history now belongs to the world, but its legacy will be measured not by its size, nor by its opening night, but by the quiet footsteps that fill its halls for decades to come.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates!

Read also:

The Louvre Robbed of Its Royal Past

The New Middle East: A Region In Flux

Rising Star: Qatar and the MENA Art Market