In October 2025, Romania officially consecrated the mosaics of the People’s Salvation Cathedral, marking the completion of a structure that now ranks as the largest Orthodox church in the world.

The building, visible from nearly every point in central Bucharest, stands 134 metres high and can hold more than 5,000 worshippers.

Construction began in December 2010 and cost approximately €270 million, financed through public funds and private donations. The project had long divided opinion. For supporters, it symbolises spiritual survival after decades of communist atheism; for critics, it reflects excess in a country still facing high poverty and emigration.

The cathedral’s completion marks a historical turning point for Romania’s Orthodox majority, which represents roughly 85 per cent of the population. Inside, completed mosaics covering 17,000 square metres depict biblical and national figures in vivid golds and reds. The ultimate planned mosaic collection will reach 25,000 square metres.

A new patriarchal residence and museum complex will open nearby in 2026.

The Political Shadow of Sacred Projects

Plans for the cathedral stretch back to the early twentieth century. They were revived in the 1990s after the fall of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s regime, when religion re-emerged as a public force in Romanian life. For many citizens, the cathedral is less about grandeur and more about reclaiming a suppressed heritage.

Romania’s post-communist governments, regardless of party, consistently supported the project. The consecration on 26 October 2025 included both religious leaders and state officials, underlining how spirituality and politics remain intertwined. Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I and Patriarch Daniel of Romania jointly led the ceremony.

Some Romanian commentators have described it as a “national altar” that seeks to reconcile spirituality with statehood. Yet critics argue that public funding for the cathedral contradicts the secular principles of the European Union, which Romania joined in 2007.

Transparency International and European Court of Auditors reports have previously questioned oversight in state-funded religious projects across the region. The Romanian government maintains that cultural heritage and tourism justify the investment.

A Tale of Two Europes

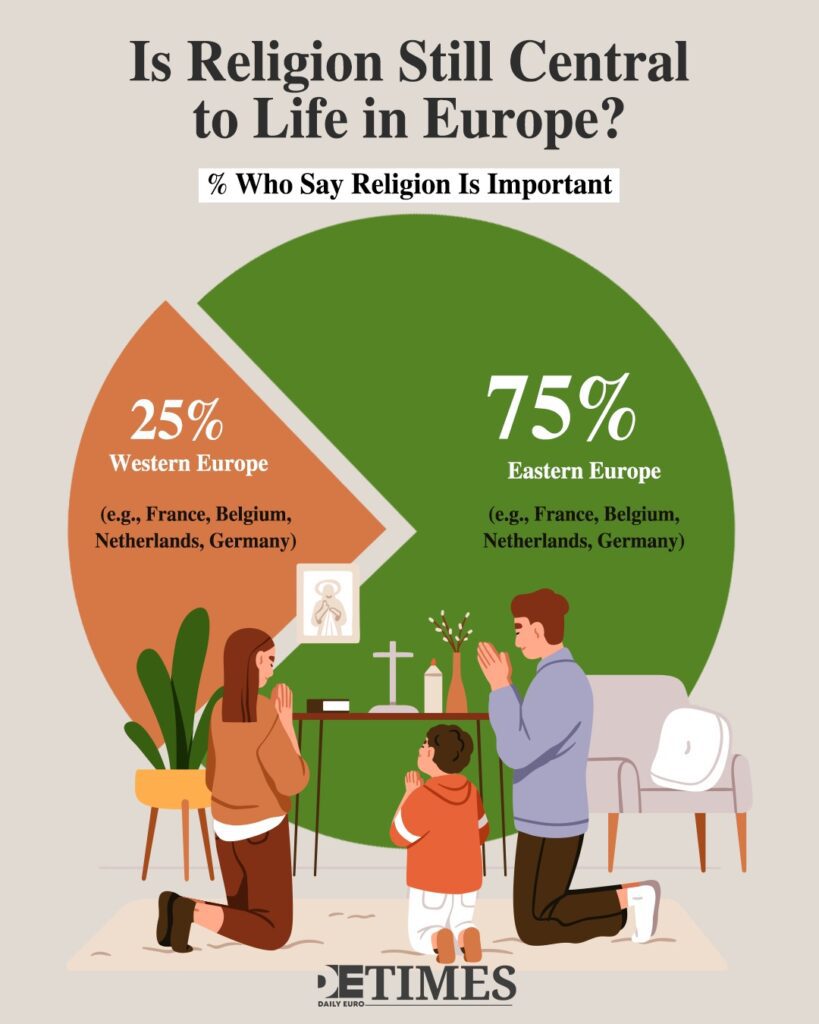

The opening of such a monumental church in Eastern Europe contrasts sharply with the religious landscape further west. In France, Belgium, and parts of Germany, churches close weekly due to declining attendance and rising maintenance costs.

In Spain and Italy, historic chapels are converted into concert halls, libraries, and restaurants.

Romania’s new cathedral stands almost as a mirror image of this trend. Here, religion is still seen as a marker of continuity and community, not merely personal conviction.

The European Values Study found that 90% of Romanians consider religion "important or very important" in their lives, compared with just 23% in France.

The difference highlights a widening cultural divide within the European Union itself: one half largely secular, the other still spiritually rooted. This divergence also has a political dimension.

In Poland and Hungary, religion has re-entered public discourse as part of national heritage, while in Romania it provides moral legitimacy to a post-communist state still defining itself within Europe.

Between Symbol and Function

The cathedral’s supporters see it as a gift to future generations. Patriarch Daniel called it “a symbol of national unity.” The project also created thousands of construction and artisanal jobs, with craftsmen from across the Balkans contributing to its elaborate interiors.

Architecturally, the building fuses traditional Byzantine design with modern engineering. Its central dome reaches higher than Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia and Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Critics, however, argue that such scale overshadows the modest traditions of Orthodox spirituality.

Claudiu Tufis, a political scientist at the University of Bucharest, told the Associated Press: “The fact that they have forced, year after year, politicians to pay for it, in some cases taking money from communities that really needed that money, indicates it was a show of force, not one of humility and love of God.”

Beyond symbolism, practical questions remain. Can such an enormous site sustain itself financially through donations and tourism? Romania’s Ministry of Culture expects it will attract more than one million visitors annually, but experts warn that maintenance costs could exceed €10 million per year.

The Meaning of Magnitude

Europe’s largest church stands as both a religious achievement and a cultural statement. Its completion at a time when observance elsewhere is fading says something profound about how different parts of Europe interpret modernity.

In Western capitals, progress often means secularisation. In Eastern ones, it can mean rediscovering religion after repression. Both paths emerge from history rather than ideology.

The People’s Salvation Cathedral embodies this paradox. It represents renewal, but also unease: the tension between spiritual aspiration and material display. For some, it offers a sanctuary. For others, it symbolises the state’s need to anchor collective memory in religion when other narratives falter.

As Europe debates its cultural future, the sight of golden domes rising over Bucharest invites reflection. Religion, it seems, has not vanished from the continent; it has simply changed its address.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates!

Read also:

Cardinal Robert Prevost: A New Era for the Catholic Church

Defence: NATO’s New Strategy in Eastern Europe – Daily Euro Times

“Return Without Compromise?”: 19 EU Countries and Norway