Recently, the international community was jolted by an announcement from Botswana that sounded less like environmental policy and more like a high-stakes diplomatic ultimatum. The nation warned that it might relocate up to 40,000 elephants abroad, specifically targeting Germany as a potential recipient of the African nation’s elephant population

This statement, which suggested a massive logistical undertaking of moving some of the world’s largest land mammals across continents, was initially reported as eccentric, or even a comedic piece of political theater. Social media was briefly flooded with generated images of elephants wandering through the Black Forest, and many commentators treated the proposal as a mere environmental curiosity.

However, the proposal was neither accidental nor whimsical. It was a calculated political message sent through animals, aimed directly at Western governments and campaigners who praise wildlife protection from the comfort of distance while rarely sharing its tangible costs.

When Botswana hinted at this mass export, it effectively translated years of rural frustration into a global spectacle. The message was clear: if the world views these animals as a global heritage, the world must be prepared to host them, or at least pay for the consequences of their presence.

The Heavy Price of Conservation Success

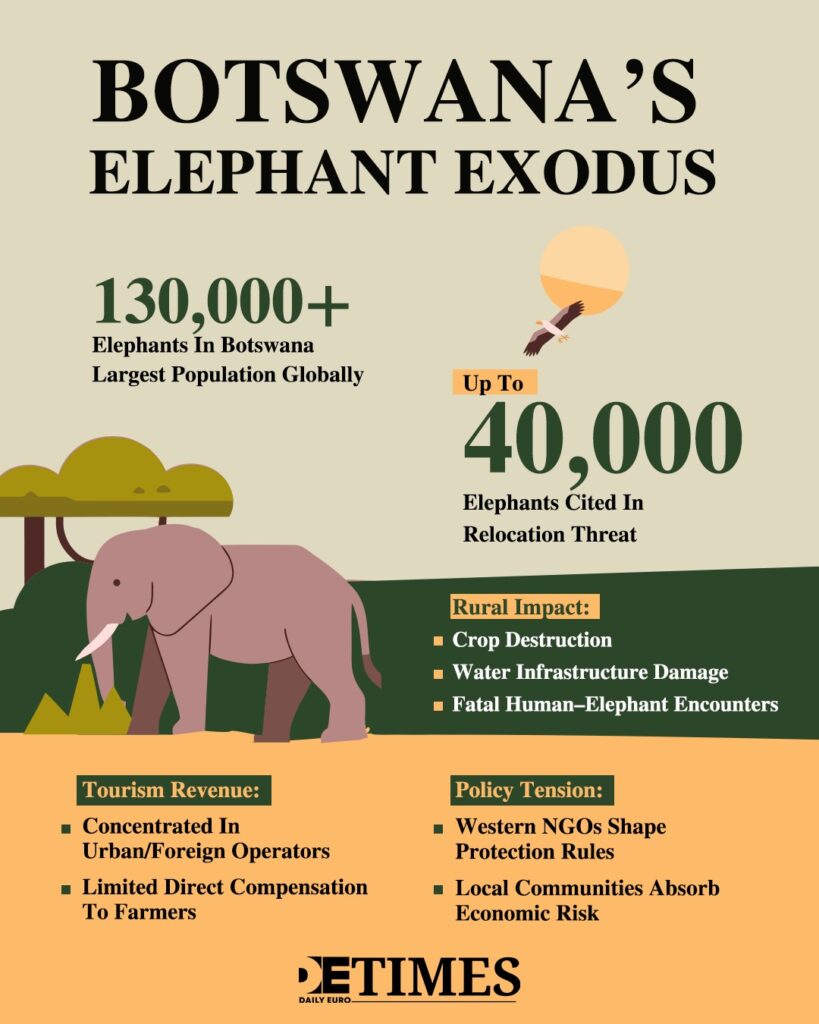

Botswana currently hosts the world’s largest elephant population, estimated at more than 130,000 animals. This is, by many metrics, a conservation triumph born from decades of protection, strict management, and relatively low poaching rates compared to its neighbors.

However, this success has brought immense internal pressure. When elephant numbers exceed the carrying capacity of their environment, they stop being symbols of nature and become a direct threat to human survival.

In rural areas, encounters are part of daily life, and the consequences are often devastating. Elephants destroy essential crops, damage water infrastructure during droughts, and sometimes kill people. For these villagers, elephants are not distant, majestic icons of the wild; they are dangerous neighbors with tusks. The “export” threat was a reaction to the disconnect between those who view conservation as a moral abstraction and those for whom it is a daily, physical risk.

By suggesting a mass relocation, Botswana’s leadership asked a sharp question: if the West values these animals so highly, why shouldn’t they take responsibility for the space and safety required to house them?

The Financial Reality of Selective Empathy

While international organizations often present Botswana as a model of wildlife management, the financial reality on the ground is far more complex.

Funding and tourism revenue certainly flow into the country, but the distribution of these benefits remains notoriously uneven. Farmers whose entire year’s harvest is flattened in a single night by a wandering herd are rarely reimbursed in full. Insurance for such losses is scarce, and relocation schemes are prohibitively expensive for local budgets.

This creates a “selective empathy” where certain species receive global protection based on their branding and emotional appeal in documentaries, while the economic needs of the people living alongside them remain negotiable. This emotional hierarchy shapes funding and international pressure, rewarding visibility more than proximity. For communities living with wildlife, admiration from afar offers little practical relief.

Protection is celebrated globally, but its consequences are absorbed locally, creating a responsibility gap that has reached a breaking point.

Tourism, Land, and Economic Leverage

Wildlife tourism is often touted as the ultimate solution for conservation funding. Safaris, lodges, and guiding services depend on healthy, visible populations of “charismatic megafauna” like elephants.

Yet, the profits from these ventures are often captured by urban operators and foreign companies, leaving villages near the reserves with little return. When tourism replaces agriculture as the primary economic justification for land use, local residents often lose both their acreage and their leverage.

Conservation thus becomes profitable for some and costly for others. When the survival of a village depends on crops that elephants find delicious, and the survival of a lodge depends on those same elephants being present, a conflict of interest arises that tourism revenue rarely solves for the common farmer.

Botswana’s recent political posturing highlights that if conservation is to be sustainable, it cannot simply be an industry that benefits the global elite while the local population remains collateral damage.

Sovereignty and the Resistance to Foreign Curation

The threat to “export” elephants also reflected a broader assertion of sovereignty against what many Southern African leaders view as environmental neo-colonialism. Wildlife policy in the region is increasingly shaped by international pressure, donor priorities, and foreign-led campaigns that originate far from the affected areas. Restrictions on ivory trade, hunting bans, and specific management methods are often dictated by Western NGOs, and local authorities must often comply or risk severe reputational and economic damage.

The elephant threat signaled a firm resistance to this hierarchy. It reminded observers that ecosystems are not museums curated by people living thousands of miles away. By challenging the authority of those who advocate for total protection without providing for management, Botswana asserted its right to handle its own natural resources.

Management replaces mere ecology when the survival of a nation is at stake, and the message served to remind the world that African nations are partners in conservation, not subordinates.

Beyond the Spectacle: A Search for Partnership

Ultimately, the proposal was never truly about transport; it was about recognition. It exposed a significant gap in the global community’s approach to biodiversity. While the world gains cultural capital, research, and tourism from Africa’s wildlife, the responsibility for maintaining that biodiversity remains fragmented. Botswana’s warning asked whether conservation is truly a collective global effort or merely an outsourced burden.

Most likely, no elephants will actually arrive in Germany. However, the message has already traveled much further than any crate ever could. Conservation that relies on admiration but avoids accountability cannot last in the long term. Wildlife protection only works when those living alongside animals are treated as stakeholders and partners, not obstacles to a Western ideal of “the wild.” Until a more equitable system of burden-sharing is established, elephants will continue to carry more than just memory and symbolism; they will carry the weight of unresolved human politics.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates!

Read also:

Steel to Startups: Germany’s Search for New Growth

East Germany: Cheap Rent to Live in a Ghost Town

Africa on Stream: IShowSpeed and a New Online Map of the Continent