NOTE: This article was written by DET’s Editor-in-Chief, Gus Anderson, with exclusive commentary from Moustafa Ahmad, Political Analyst in the Horn of Africa, and Associate Professor and Director of MENA analytica: Dr Andreas Krieg.

The Horn of Africa is once again grabbing headlines with rumours of U.S. recognition of Somaliland on the horizon. Reality, however, is more complicated. Beyond the noise and disinformation, real shifts are underway even if they fall short of formal recognition. In a striking first, Qatar hosted Somaliland President Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi Irro in June.

At the same time, Ankara presses ahead with oil exploration off Somalia’s coast while stoking secessionist unrest in Las Anod and now the Awdal region of Somaliland. Doha’s outreach was no accident: it reflects a broader recalibration across the Gulf as Washington signals a rethink of its Africa policy and GCC states hedge against dependence on their traditional security provider.

Moustafa Ahmad, Political Analyst of the Horn of Africa: It appears that many actors in the international community are disappointed with Somalia’s trajectory and are obviously looking for alternatives elsewhere, primarily in Somaliland, he argues.

Doha’s Shift: Irro’s Visit and Al Jazeera Arabic

For years, Doha has backed Mogadishu’s “One Somalia” line with little ambiguity. It positioned itself as a mediator in regional disputes, from Somali politics to the Mogadishu-Nairobi rift, while aligning with Mogadishu’s agenda.

Irro’s official invitation to Doha broke that mould, whilst it may also “reflect Somaliland’s awareness that Hargeisa needs to expand and diversify its international partnerships” according to Horn of Africa political analyst: Moustafa Ahmad. It signalled alarm at the pace of change in the Horn, especially as U.S. lawmakers – including Senator Ted Cruz – push for recognition after a high-profile AFRICOM visit to Hargeisa.

Moustafa Ahmad: “Qatar’s invitation of Irro could also represent the small emirate’s frustration with Somalia’s prolonged crises and might use the trip to explore possible working relations with Hargeisa.”

Al Jazeera Arabic: Symbol of Qatar’s Hedge

Doha’s media mouthpiece, Al Jazeera Arabic, substantiated the significance of U.S. support.

Within days, the platform outlined the case for Somaliland’s recognition, whilst celebrating the recognition of the self-declared “SSC-Khatumo” state in Las Anod. The mixed signals reflect Qatar’s attempt to straddle a shifting landscape: extending one hand to Hargeisa as U.S.-Somaliland ties deepen, while undercutting recognition by amplifying clan rivalries.

Washington’s Rethink

U.S. officials have long acknowledged Somaliland’s democratic institutions and strategic location by the Gulf of Aden. Yet Hargeisa’s failure to control its eastern province, specifically in Las Anod, has fuelled caution in Washington and across the African Union wary of granting support for independence if it means “more secession.”

Trump’s return to the White House has jolted the calculus. His “America First” foreign policy has meant aid cuts, USAID retrenchment, and a new focus on minerals, defence partnerships, and migration control. Africa has moved up the list of strategic priorities, with Somaliland in play.

The White House still officially recognises Somalia’s territorial integrity in theory. Yet Trump’s transactional approach leaves room for deals that exchange U.S. access – ports, minerals, counterterrorism cooperation – incremental moves toward Somaliland’s de facto recognition.

U.S. policy moves on Africa and recent statements by the President suggest it is all to play for, on Somaliland, as Trump confirmed in a press conference between Azeri and Armenian leaders: “We are looking into that.”

Instability in Somalia

Somalia remains on the back foot. Al-Shabaab is advancing near Mogadishu while the African Union force struggles for resources and support. In the north, Daesh cells persist despite counter-smuggling efforts by Puntland, U.S., and Emirati forces across the Gulf of Aden.

This fragility heightens Somaliland’s value as a functioning partner.

For Washington, Somaliland offers a foothold in a maritime hub prone to arms smuggling, proxy wars, and corruption.

For Doha, it presents a dilemma: stick with a weakening partner in Mogadishu or pivot toward Hargeisa without undermining its self-styled role as regional mediator.

Abu Dhabi, Israel, and the East African Corridor

President Irro’s trip will be crucial in the face of growing voices in Washington to recognise Somaliland.

The UAE has poured investment into Somaliland through DP World, embedding itself in East Africa’s infrastructure. The Berbera Corridor, underpinned by Emirati capital, is fast becoming a backbone of regional integration: connecting the upgraded Port of Berbera to Ethiopian markets.

Security cooperation between the Emiratis and Israelis points to another dimension: joint counterinsurgency against Houthis and smuggling routes in the Gulf of Aden out of Berbera port. For Washington, closer ties with Hargeisa align with Washington’s bid to integrate Israel via normalisation, whilst supporting Emirati and Israeli strategic interests.

According to Dr Andreas Krieg, Associate Professor and Director MENA analytica: "The UAE and Israel have become increasingly aligned in Africa, especially in strategically located areas like Somaliland. Both states share a view of Africa not only as a market and diplomatic frontier, but as a geostrategic corridor — critical for maritime access, military basing, and regional influence.

In Somaliland, this alignment has manifested through parallel and occasionally overlapping initiatives. The UAE has heavily invested in the Berbera Port, secured security partnerships, and cultivated ties with Somaliland’s leadership independently of Mogadishu. Israel, while less overt, has shown signs of coordination — notably through intelligence cooperation, quiet diplomatic outreach to Hargeisa, and reported interest in Berbera as a potential surveillance and logistics node tied to Red Sea and Gulf of Aden operations.

What binds the UAE-Israel alignment is their shared suspicion of political Islam, their regional rivalry with Iran, and a preference for working with sub-state or autonomous actors when central governments are weak or unreliable. Somaliland’s non-Islamist, relatively stable, and pro-Western orientation makes it an attractive partner. This alliance also undermines Qatari and Turkish influence in the Horn," said Dr Krieg.

Gaza and GCC Competition

The Horn’s shifting dynamics cannot be separated from Gaza. Abu Dhabi’s growing influence in Somaliland and East Africa coincides with its role in shaping “day after” scenarios in Gaza – whether through civilian governance or outright annexation.

In both theatres, Qatar risks marginalisation where it’s attempt to mediate between Hamas and Israel has failed due to Israeli internal divisions whilst it’s ability to mediate between Somali clans is increasingly irrelevant.

Qatar's outreach this week to African nations, promising funds in exchange for influence confirms the recent overtures Doha is making to keep up with the Chinese and Emiratis in Africa. It comes as UAE President Sheikh Al-Nahyan visited Angola this week.

The Europeans may recognise Palestine, but without sanctions or leverage on Israel, Doha sees the writing on the wall. To stay relevant, it must carve out a space in the Horn – if only to avoid being excluded from another regional arena.

A Challenge to Qatar to be Washington’s Broker of Choice?

The UAE’s increased involvement in brokering deals across Africa (which is not at all the same as mediation) is part of a broader networked effort to present itself to Washington, Beijing and Moscow as a reliable diplomatic partner capable of managing regional crises. Through high-level engagement in ceasefire negotiations, reconstruction efforts, and elite-level diplomacy, Abu Dhabi is seeking to elevate its status from a transactional actor to a geopolitical convener.”

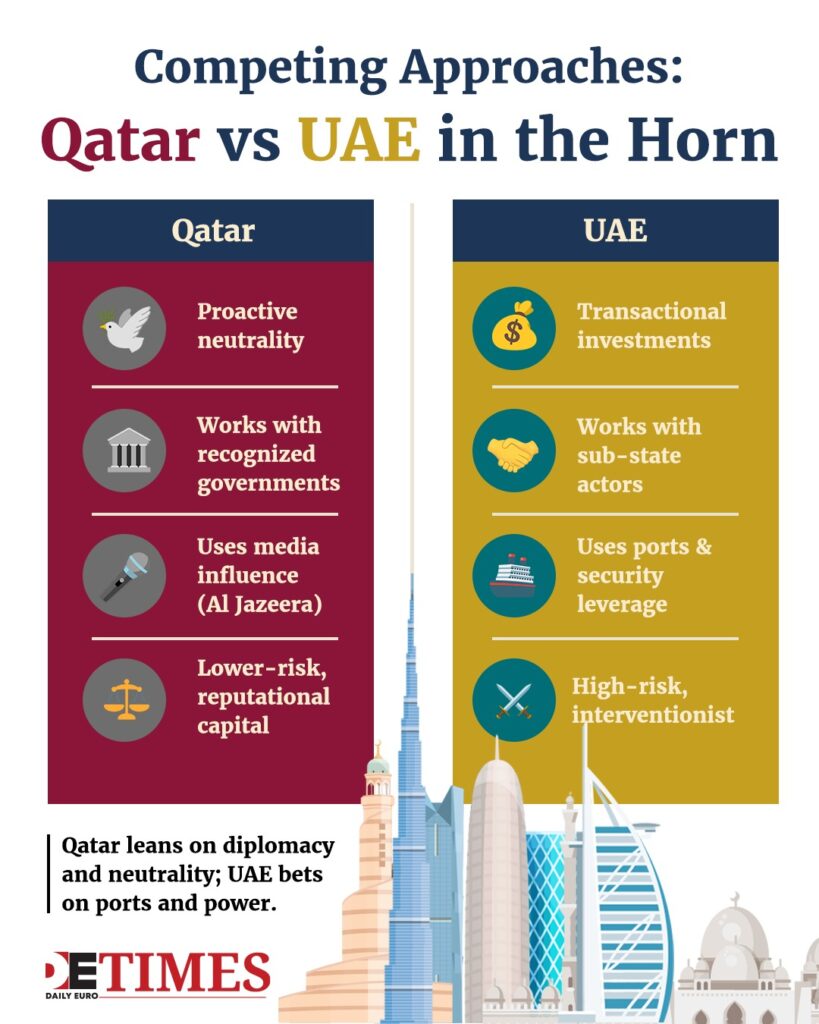

However, Dr Krieg said that "Qatar’s position as a trusted and proactively neutral mediator remains more credible and sustainable, particularly in theatres where legitimacy and impartiality are prerequisites for successful diplomacy. Qatar does not intend to compete directly with the UAE in arenas where the Emiratis have already heavily invested, such as eastern Libya or Somaliland.

Instead, Qatar has deliberately adopted a far less high-risk, lower-profile approach, prioritising strategic patience, reputational capital, and relationships with recognised governments and international institutions."

Two Contrasting Approaches: The Qatari and Emirati Models

The contrast between the two approaches is sharp.

“Qatar’s model is built on proactive neutrality — maintaining open channels with all sides while avoiding entanglement in local factionalism. It seeks to mediate from a position of perceived fairness, often working quietly through regional and multilateral frameworks. In contrast, the UAE’s model has been based on cultivating deep ties with sub-state entities and secessionist movements, providing financial, military, and diplomatic support to actors such as the LNA in Libya, the RSF in Sudan, and political elites in Somaliland and other Somali provinces.

Krieg: "This strategy, while effective in expanding influence in the short term, is now backfiring in multiple theatres."

In Sudan, the UAE’s support for rival factions has been widely criticised for exacerbating fragmentation and undermining peace efforts. In Libya, Abu Dhabi’s deep entrenchment with one side has made it difficult to play a unifying diplomatic role. These experiences are damaging the UAE’s ability to present itself as a neutral broker — a role that Qatar continues to play more effectively.

As a result, Qatar retains more credibility in the eyes of both African actors and Western policymakers, particularly those within multilateral institutions and the U.S. State Department. Its restrained, state-centric approach is aligned with African Union principles and international norms, which emphasise territorial integrity and national sovereignty — a contrast to the UAE’s more interventionist posture.

While the Trump administration may find tactical alignment with the UAE’s more muscular diplomacy, Qatar’s long game — grounded in discretion, neutrality, and respect for sovereignty — gives it enduring leverage as a diplomatic facilitator, especially in situations where inclusive dialogue and trust-building are prerequisites for progress,” said Dr Krieg.

What Next for Doha?

The outcomes of Irro’s U.S. visit will define Doha’s next steps. Three scenarios loom:

- Symbolism Only: Irro meets U.S. officials but secures no concrete concessions, as Washington keeps recognition at arm’s length.

- Strategic Access: Washington secures port and mineral deals in Berbera, deepening security ties while stopping short of recognition.

- Full Breakthrough: The U.S. recognises Somaliland outright in exchange for military and resource access; a seismic shift in regional policy.

Moustafa Ahmad: “Doha’s engagement in Somaliland is less a sign of policy change and more of a hedge. Qatar is seeing the ground shifting in the Horn and wants to maintain its position of influence in the foreseeable future. So I see its hosting of President Irro as a preparation for the possible scenarios unfolding in the region now.”

The third remains unlikely. The second security and economic partnership without formal recognition is the most probable. This would align Washington with UAE and Israeli priorities while keeping its policy flexible.

According to Dr Andreas Krieg: "There is movement around the question of recognising Somaliland in the Trump administration due to heavy Emirati lobbying. But there has been no informed reflection in Washington about the long-term consequences of such a move for US Africa policy. The upcoming visit of Irro to Washington, backed by voices like Senator Ted Cruz and a growing bloc of lawmakers advocating for US recognition, signals a political moment that Somaliland is eager to capitalise on.

Trump’s foreign policy style is deeply transactional, and he is known to favour partners who offer strategic assets without demanding entangling alliances. Somaliland’s offer of a U.S. base in Berbera — which could serve as a counterweight to China’s presence in Djibouti and even reduce dependency on Qatar’s Al Udeid — fits this logic.

However, a full diplomatic recognition of Somaliland remains a high-stakes gamble. It would undermine Somalia’s territorial integrity, place the US at odds with the African Union (whose consensus firmly opposes secessionism), and alienate regional partners like Ethiopia and Kenya. Trump may be more likely to pursue a semi-formal upgrade of ties — such as opening a liaison office in Hargeisa, expanding military cooperation, or designating Somaliland as a “security partner” — without full recognition. Such a move would signal strategic interest while preserving ambiguity.

If that happens, Qatar and Türkiye — which strongly supports Somali unity — would likely respond by redoubling efforts to shape US thinking through backchannel diplomacy, leveraging its deep ties in Washington and Mogadishu. It could also present itself as a mediator in any future talks between Somalia and Somaliland to preserve its image as a proactively neutral broker, Dr Krieg added.”

What the Meeting Means?

Doha’s invitation to Irro was more than symbolic; it was defensive. Faced with U.S. transactionalism, Emirati capital, and Israeli security partnerships, Qatar is scrambling to avoid being sidelined.

The Horn of Africa has always been a prize. Now, with Trump back in the White House, its future may hinge on minerals, ports, and counterinsurgency more than sovereignty or democracy.

For Somaliland, this opens the door to unprecedented leverage. For Doha, it raises a question it cannot avoid: can Qatar remain a serious mediator in a region where Abu Dhabi is already setting the terms?

NOTE: This article was written by DET’s Editor-in-Chief, Gus Anderson, with exclusive commentary from Moustafa Ahmad, Political Analyst in the Horn of Africa, and Associate Professor and Director of MENA analytica: Dr Andreas Krieg.

Read Other Articles at DET!

Exclusive: Somalia, Recognition, and Normalisation

Triangular Diplomacy: Djibouti, the Houthis, and Somalia

Qatar to Brussels: No LNG Without Respect