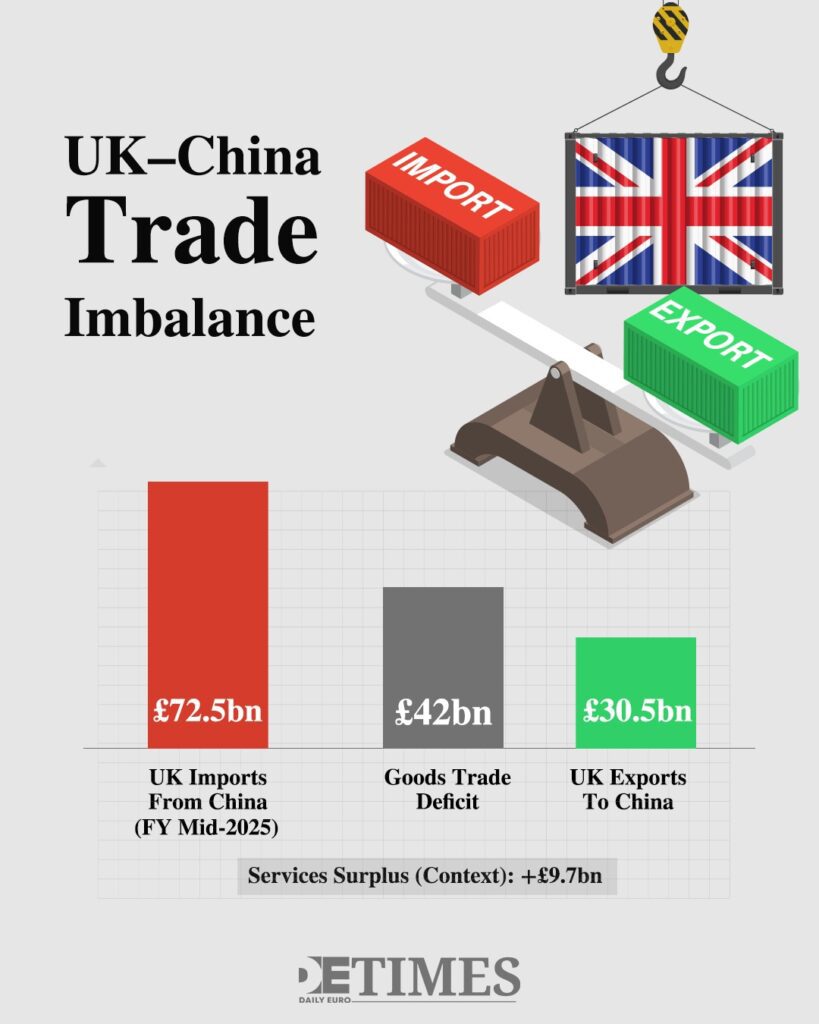

Commercial records for British procurement of Chinese goods surged to £72.5 billion in the fiscal year ending mid-2025, even as British sales to the Chinese market receded by 10.4 per cent to £30.5 billion.

This widening asymmetry in the exchange of goods confirms an undeniable trend that now sits at the heart of the government’s economic agenda.

The goods deficit has tripled compared to 2007 levels, gaining speed in the years following 2020. Such a trajectory carries weight far from Westminster, as Washington observes whether a long-term ally’s enduring security will be compromised by immediate fiscal pressures and the allure of near-term growth.

A Mercantilist Mission Amidst Changing Tariffs

Seeking to reinvigorate a dialogue dormant since 2019, Chancellor Rachel Reeves visited Beijing and Shanghai in January.

Accompanied by Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey and senior banking leaders, the Chancellor negotiated agreements worth £600 million for financial services and agriculture, signaling a desire to repair fractured commercial ties.

The Chancellor framed economic expansion as the government’s absolute mandate during her visit to a Beijing bicycle shop. Downing Street seeks to erode barriers for British firms as exports to America contracted by £2 billion because of new Trump-era trade protocols that have already begun to reshape transatlantic commerce.

Donald Trump convened with Xi Jinping in South Korea on 30 October 2025 to discuss minerals and fentanyl. Both administrations established a 30 per cent baseline tariff on Chinese goods following a cycle of extreme escalation. Washington deployed steep duties, prompting Beijing to restrict exports of semiconductor materials in a calculated display of industrial leverage.

The Gravity of Trade Imbalances

The current imbalance occurs because China focuses its economy on building more goods than its own citizens can buy, which forces it to ship the extra production abroad. Britain remains a major destination for Chinese electronics and consumer goods, although the United Kingdom attained a £9.7 billion surplus in services to provide a partial counterbalance to the heavy flow of manufactured imports.

Digital strengths in finance and law now constitute nearly half of all British exports to China. Because such sectors bypass physical border friction, they offer a specialised counterweight to a manufacturing base that saw a 23.1 per cent drop in exports to China in a single year, highlighting the shift toward an intangible trade relationship.

An American Eye on British Commerce

The President-elect’s opposition to trade gaps makes London’s Chinese commerce a source of friction with the White House.

Chinese officials have already denounced U.K.-U.S. pacts as a surrender to American containment strategies, placing London in a difficult position between its primary security partner and its most significant source of imports.

Britain’s partners are increasingly sensitive to strategic reliance. Security concerns regarding technological transfers complicate trade, and although European countries managed the economic security demands of the previous administration, the current American posture has introduced a new level of volatility to the global order.

Europe’s broad reliance on China for raw materials has allowed Beijing to deploy export controls as a diplomatic tool. In negotiations between Washington and Brussels, rare earth elements have become Beijing’s primary source of leverage, often dictating the terms of engagement in the green energy sector.

The Economic Toll of Geopolitical Affiliation

London feels pressure to adopt American security protocols, including restrictions on Chinese digital platforms and academic collaborations.

Choosing that course includes thwarted investment in British tech firms and universities, which are heavily supported by Chinese tuition fees and research partnerships that are difficult to replace.

At the heart of the government’s predicament is the erosion of national resilience. Without a careful strategy, Britain risks an entrenched reliance on Chinese intellectual property for its energy grid and transport infrastructure, creating long-term vulnerabilities that transcend simple trade statistics.

The geopolitical chill is already evident in capital flows, as British direct investment in China shrank by 20.3 per cent by the end of 2023, while Chinese investment into the U.K. has similarly slowed. Such a cooling manifests a world where geopolitics dictates the boardroom and investment decisions are increasingly filtered through a security lens.

Metrics of Persistent Asymmetry

The metrics are immune to political framing.

From a modest share of British exports in 2019, bilateral trade with China has expanded to £103.1 billion in 2024. As Britain looks toward a scheduled state visit to Beijing in early 2026, it will require a plainer understanding of the American direction before committing to further integration.

A trade deficit quantifies a country’s reliance. Britain’s £42 billion gap with China is a reality that persists regardless of London’s diplomatic vocabulary or political aspirations. Washington monitors the tallies irrespective of how Westminster frames the data, viewing the numbers as the ultimate indicator of strategic alignment.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates! Read also:

From Belfast to Gaza: Britain’s Attempt to Export the Good Friday Agreement

Britain’s New Empire of Arms: Keir Starmer’s Missile Diplomacy in India

Britain Closes Its Doors, Portugal Follows: The New Face of European Refugee Policy