Nigel Farage’s “anti-woke” Christmas event in London on 19 December turned a religious and family holiday into another theatre of cultural anxiety.

The message was simple: Christmas belongs to a certain idea of Britain, and that idea must be defended from modern sensibilities and social change.

Beneath the headlines, though, lies an awkward truth. The Christmas being defended was never pure in the first place.

A Festival of Borrowed Customs

What people now recognise as Christmas is the outcome of centuries of mixing.

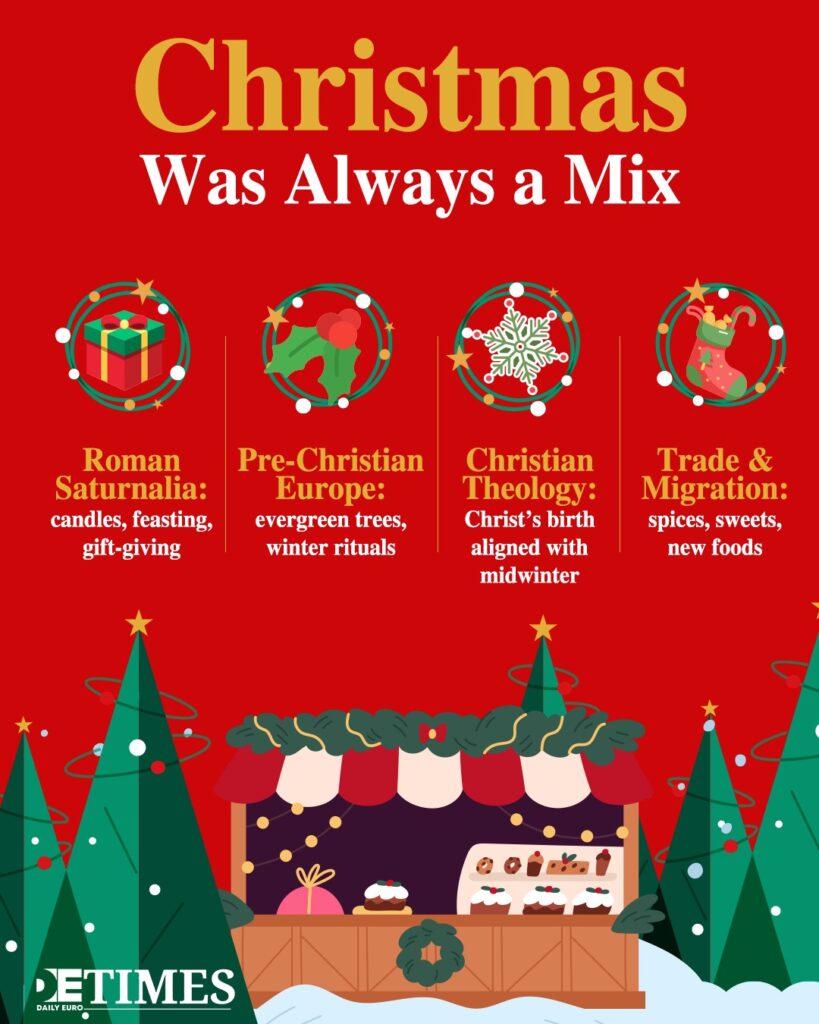

Early Christian leaders chose late December for the celebration of Christ’s birth partly because the date overlapped with existing midwinter rituals.

Saturnalia brought feasting, candles and small gifts in the darkest days of the year, customs that survive in today’s seasonal markets and office exchanges. The evergreen tree so central to northern living rooms owes as much to pre-Christian reverence for fir and oak as it does to church calendars.

Even the idea of a “traditional” Christmas menu varies wildly, from fish in southern Italy to spiced cakes in the Balkans and roast lamb in parts of the eastern Mediterranean. In other words, Christmas has always been a negotiation.

Local cultures absorbed Christian symbols into older seasonal habits. New foods arrived with trade and migration. The result is a holiday that looks unified on postcards but changes from street to street.

Politics Tries to Freeze a Moving Target

The recent British event is only one example of politicians using Christmas as a stage on which to play out fears about identity. Some complain that “inclusive” greetings dilute faith. Others say that any public reference to religion excludes non-Christians.

Both positions overlook how adaptable the festival has always been. In cities from Paris to Berlin, Christmas markets now coexist with Hanukkah celebrations and, in some neighbourhoods, with restaurants serving special menus for people who do not observe either.

In parts of North Africa and the Middle East, Christian minorities observe the season under very different political and social conditions, but still share its lights, sweets and carols with Muslim neighbours. Rather than corrupting Christmas, this diversity continues its oldest habit: absorbing whatever the surrounding society brings.

Food, Commerce and Quiet Hypocrisy

There is also the small matter of money. Even as some public figures denounce “woke” Christmas marketing, British high streets lean heavily on the holiday to sustain winter sales.

Supermarkets advertise “traditional” menus using ingredients shipped across continents. Luxury brands sell limited-edition Advent calendars, whilst budget chains promote plastic decorations that have little to do with any faith.

None of this is new. Medieval towns already saw December as a time for special food and extra spending. The difference today is the speed and scale of global supply chains, and the way advertising wraps consumer habits in the language of authenticity.

If Christmas has become harder to recognise, it is less because anyone says “happy holidays” and more because a season once tied to local calendars is now packaged as a standardised lifestyle product.

A Holiday that Still Belongs to Everyone

Mixed-diet families, interfaith couples, secular households and devout believers all navigate the season in their own ways. One home might place a nativity scene next to a plastic reindeer. Another might share the food and lights whilst skipping the church service.

A third might ignore the day altogether. That variety does not weaken Christmas. It reflects what the festival has always been good at: providing a shared winter pause in which people can eat better, sit closer and forget, briefly, the rest of the year’s noise.

Calls to “defend” Christmas often assume there was once a single, correct version of it. History suggests something else. The holiday that now fills squares and living rooms came from mixing rites, northern forests and Near Eastern theology, then letting centuries of families alter the details.

If anything, remembering this might lower the temperature of today’s arguments. Christmas is many things at once: Christian feast, secular break, family ritual, economic engine.

It was hybrid long before anyone used that word. Perhaps the most traditional thing people can do this year is accept that simple fact and get on with sharing the table.

Keep up with Daily Euro Times for more updates.

Read also:

Religion as Tradition: Romania and the CEE Defy Europe’s Secular Turn

McDonald’s AI Christmas Ad Backlash: Audiences Reject Synthetic Sentiment

When the Angels Return: How Victoria’s Secret is Shocking the New Era of Beauty